Courtesy of the Hood Museum of Art.

Courtesy of the Hood Museum of Art.

During the first week of my freshman year at Dartmouth, while attempting rather unsuccessfully to navigate Baker-Berry Library, I found myself face-to-face with an imposing sight: The Epic of American Civilization, Mexican muralist José Clemente Orozco’s magnum opus. It was an exciting discovery, not only because the mural was physically awe-inspiring, but also because it wasn’t my first time seeing it. I had studied Orozco’s mural in my high school AP Art History class, but failed to realize it was housed in my college’s library until I was three feet away from it. The mural is among Dartmouth’s greatest treasures, and was designated a national historic landmark this year.

Orozco painted his mural from 1932 to 1934, when he was in-residence at the College. The content of the mural is not uncontroversial; The Epic of American Civilization offers a radically revised narrative of American history, in which European migration to the Americas leads to an apocalyptic modern era characterized by destruction and greed. Orozco was a practitioner of social realism, and the mural showcases his opinions on capitalism, higher education, Christianity, and other aspects of American society he found unsavory.

Whereas students, faculty, and art critics were largely enamored with Orozco and Dartmouth’s bold experimentation with modern art, alumni were violently critical of Orozco’s mural. Among the enraged alumni was Walter Beach Humphrey, a member of the Class of 1914. Humphrey, an illustrator and muralist whose work adorned the covers of the Saturday Evening Post and Collier’s, painted in the colorful, humorous style of America’s best-loved illustrator, Norman Rockwell. The similarities in style are unsurprising—the two illustrators shared a studio at one point. College president Ernest Martin Hopkins supported Orozco’s mural as a matter of principle, but agreed to allow the angry alumni the opportunity to create a mural of their own. From 1938 to 1939, on commission by the Trustees of the College, Humphrey painted four scenes inspired by “Eleazar Wheelock,” a Dartmouth drinking song written by Richard Hovey, Class of 1885, who also penned Dartmouth’s Alma Mater. The “Hovey mural,” as it is called, would decorate a rathskeller in the basement of Thayer Dining Hall (now Class of 1953 Commons), and act as a counterpoint to Orozco’s fresco on the other side of campus.

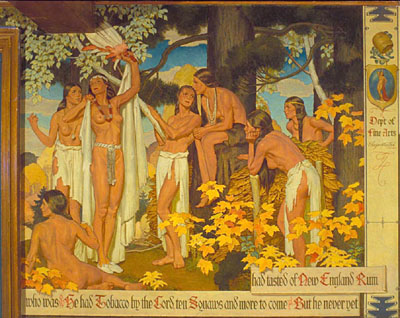

The mural depicts a jovial and plump Eleazar Wheelock entering the wilderness with “five hundred gallons of New England rum” to “teach the Indian,” as Hovey’s lyrics dictate. Wheelock “mixed drinks for the heathen in the goodness of his soul,” and the “big chief matriculated” in a College whose “whole curriculum was five hundred gallons of New England rum.” The rambunctious male Indians in the mural are pictured eagerly indulging in Wheelock’s rum, while half-naked female Natives look on.

The Hovey mural was considered innocent and comical by most in its first few decades of existence, but the advent of coeducation and the Native American Studies Program in the 1970s put the mural at the center of a heated debate over Dartmouth’s white male-dominated culture. Because of the controversy the mural engendered, the room that houses it was closed in 1979, and the paintings were covered in 1983. The paintings were opened for commencement and reunions, but this practice was discontinued in the 1990s. The Native American Council at Dartmouth initially suggested the murals be uncovered and viewed in conjunction with a program written by Native American students, but the council eventually decided against this, reasoning that it was not the burden of Native students to explain the offensive nature of the mural.

Today, the Hood Museum of Art provides a didactic program on the mural, and the room that houses it is opened periodically for classes that have discussed the mural in an academic context. I was fortunate to see the Hovey mural firsthand as part of my freshman seminar, a Native American Studies class taught by Melanie Benson Taylor. The mural is as aesthetically pleasing as its content is morally ambiguous, and I feel privileged to be one of the few Dartmouth students to even know the mural exists. What was once a prominent work of art and subject of fierce debate has become an obscure relic of “Old Dartmouth,” swept under the rug and left unknown to the majority of Dartmouth’s students. This development begs the question: Should the mural remain closed to the public? Is there merit to restricting the number of people who are allowed to view it, or does this tactic amount to censorship?

In The Hovey Morals at Dartmouth College: Culture and Contexts, several Dartmouth professors provide insight into the history of the mural and comment on Humphrey’s controversial depictions of Natives. Professor Emeritus of Art History Robert McGrath contends that the mural’s depiction of Indian males enthusiastically imbibing is a representation of Humphrey’s views on the Dartmouth experience in the 1930s. Professor McGrath believes the mural “is not about Indians and clergymen, nor is it much concerned with historical accuracy about the founding of Dartmouth College… it is at one important level a metaphor for the ideals of Dartmouth manhood, the ‘homosocial’ as understood at the time of the mural’s execution.” Humphrey was not alone in romanticizing the role that drunken revelry played in fraternal bonding at Dartmouth; in 1938, Dartmouth Alumni Magazine described the murals as “appropriate to the masculine atmosphere of Dartmouth.” It is reasonable to assume that Humphrey intended the mural to be an embodiment of Dartmouth’s ‘homosocial’ ideals of manhood, not a commentary on the role of Natives in American culture.

Rayna Green, Director of the American Indian Program at the National Museum of American History, does not subscribe to Professor McGrath’s assertion that the mural is merely a commentary on manhood at Dartmouth. Green argues that Humphrey fully understood “how powerful a wedge Indians might be in the battle for the American imagination. So his Dartmouth Indians, unlike Orozco’s Indians, are rooted quite deeply in the centrality of Indians to the great national mythologies.” Professor Melanie Benson Taylor also contends that Humphrey had an explicit agenda in his portrayal of the Indians: “Threatened by men and movements like Orozco, Humphrey labored to emblazon and protect on the walls of the Hovey Grill a sweeping American colonial narrative… a fiction that he needed to make ‘real’ in order to preserve its ideological command.” Based on this interpretation, Humphrey’s cartoonish Indians served to deliberately reinforce the romanticism of the American national identity, and counter the unpleasant realities of settlement politics Orozco portrayed in his mural.

The two aforementioned interpretations of the Hovey mural are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Professor Mary Coffey notes that Humphrey’s illustrations appeal to a “robust, masculine atmosphere that many white, male alumni revere,” but also examines the Hovey mural in its context as a foil to the Orozco murals. Professor Coffey calls Orozco’s mural an “appraisal of White, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant values,” also noting that it “satirizes higher education” and characterizes graduation from an institution like Dartmouth as “an empty ritual.” Humphrey and other alumni were understandably offended by the Mexican artist’s controversial interpretation of American values, and enraged by the presence of such a provocative mural on Dartmouth’s campus.

In a letter to College President Hopkins, himself a staunch defender of the murals, Humphrey displayed a rather narrow-minded understanding of modern art, arguing, “a truly great work of art is seldom a matter of serious controversy or a subject of bewilderment.” Humphrey also claimed that a commissioned artist should be “bound by the ideas of his patron or the policies of an institution… and by the type, nature, and use of the building in which he works.” Indeed, given the location of Orozco’s mural in Baker Library, its severe critique of higher education is rather incompatible with the values of the institution that houses it. However, Humphrey’s critique of contentious art is now extremely ironic, given the controversial history of his own mural. Rayna Green explains, “What neither he [Humphrey] nor his fellow Dartmouth alums ever counted on was that a later audience might see different things in his cultural history of North America than he and his original audience saw.” While Humphrey may have viewed his depiction of the wild, drunken Indians as humorous and lighthearted, his mural is irreconcilably out of place at an increasingly diverse Dartmouth College.

The Hovey mural is troubling not only because Humphrey indulged in a longstanding tradition of generalizing Native American appearances and attire; his sexualized depiction of Native women—all of whom, Professor Benson Taylor points out, are phenotypically Caucasian—and his insensitive treatment of alcoholism among Native populations can also be viewed as offensive. However, shuttering the Hovey mural raises the possibility of a dangerous precedent in our treatment of controversial art in general. In a 1976 editorial in The Dartmouth, Ted Kutscher ’74 wrote: “To cover the murals would be to deny the imperfections of our background, and to leave them in their present place would be to deny our sensitivity for the composition of our modern society.” The Hovey mural is currently opened to students for educational purposes on an extremely infrequent basis. The College should consider making it more readily available, without excusing its objectionable content. As Kutscher wrote, “If we can preserve them and present them in a way which does not condone their implications, then we will be practicing a certain amount of cultural maturity which has been a long time in coming.”

— James G. Rascoff

Be the first to comment on "The Other Mural"