A steady drumbeat of columns after November have continued to predict the upcoming demise of the American Right. From political scientists who have been predicting a decline for years (Ruy Tuxiera comes to mind) to somewhat less renowned or informed newspaper columnists opportunistically claiming a 51%-48% victory foretells the complete extermination of the smaller ideology, conservative readers can find no shortage of gloom and doom news. Certainly, very few positive policy outcomes resulted from 2012 (besides the top-ticket election loss, education reform, public pension reform, and good government reforms all also suffered high-profile referendum defeats). In addition, much incoming demographic change is indefensibly challenging to the American right. Very few think that the immediate course of action ought to be blinders on and full march forward. However, triumphalist Democrat celebrations may ring just as hollow as Rove’s oft-misquoted “permanent Republican majority”. As disappointing as 2012 may be towards true believers, many lessons taken from the cycle paint a far more mixed and nuanced picture of the future of American elections.

Much has been made of the so-called coalition of the ascendant: a grouping of demographically ascendant Latino voters and economically ascendant young white (and Asian) professionals (ala Stuff White People Like) that will propel the Democratic Party into an increasingly strong position of demographic domination. Indeed, much of urban and coastal America, as well as a variety of once-Republican immigrant gateways, have increasingly become one-party Democratic strongholds. However, even though a variety of once purple states (Nevada, Colorado, Virginia) have tinted blue, these demographic shifts have simply not translated very well into legislative influence. Republican House losses in 2012 were overwhelmingly concentrated in a handful of Northeastern and predominantly Hispanic districts, districts where the Democrats have already established total control. Even though a strong majority of votes for the House of Representatives went to Democratic candidates, the House still retains a strong Republican majority that almost certainly will not be threatened for at least a decade. A Huffington Post article lamented the evils of “Republican gerrymandering” as cause to blame by pointing out that if assuming a universal swing, the Democratic Party would have needed to crush the Republicans by over 7% in the national popular vote to simply take a narrow majority. However, the Washington Post noted that redistricting was largely a wash for both parties. Although the GOP won strong majorities in various state legislatures around the nation after in 2010 just in time for redistricting, Democratic gerrymanders tended to reap much greater rewards, such as in Illinois, Maryland, and California. Democrat control in Illinois led to the worst GOP losses in the nation, Maryland’s O’Malleymander was so contorted, the (normally very liberal) Montgomery County Democratic Party condemned it, and California’s bipartisan commission was, as pointed out by the nonpartisan investigative journalist outfit ProPublica, essentially controlled by Democratic Party operatives. The poster-child for Democratic accusations was Pennsylvania, where Democrats took the popular vote but took only five out of the state’s eighteen congressional seats. However, with the collapse of Democratic support in working-class Western Pennsylvania and the increasing dependence of the party on the urban area surrounding Philadelphia, the electorate is very much naturally gerrymandered.

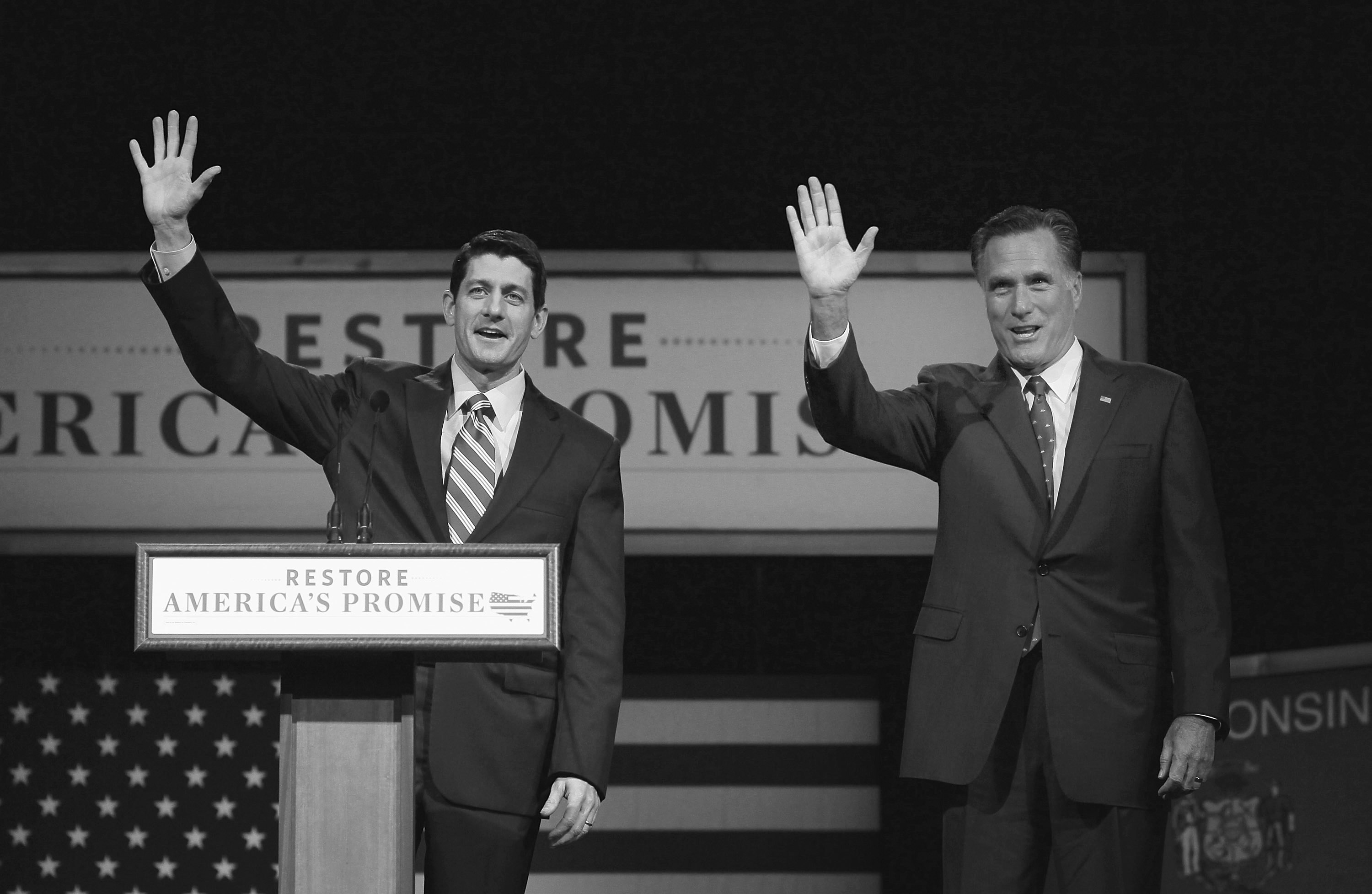

Despite all of their faults and flaws, we still love them…

Despite all of their faults and flaws, we still love them…

The nature of this so-called coalition of the ascendant is that it is built on an educational, cultural, and geographical reality that makes it far more likely for a modern Democrat to simply not know or associate with anyone holding dissenting views than vice versa. This so-called demographic ascendance has led to more Democratic voters becoming concentrated in smaller and more politically homogenous regions. Although these demographic changes have allowed Democrats to feel more confident about future Electoral College results, they have not translated into control of Congress. In addition, as shown by recent Democrat crusades on amnesty and gun control, the increasingly confident demands of these strongly left-wing supporters increasingly contradict the policy desires of the more culturally moderate voters whom the Democrats require to build a winning legislative coalition. In addition, this type of party competition does have its precedents.

Much has been stated about the necessity of the Republican Party to “restore its brand”, often by columnists who argue Republicans must adopt Democratic policy positions to remain competitive. Parallels are often drawn to 1980, when the Democratic Party was very much like today’s Republican Party, attacked for perceived extremism. However, problems exist with that line of thought. For one, like the GOP of 2012, the policy positions of the Democratic Party of 1980 were largely not extreme. A disastrous nomination in 1972 (acid, amnesty, and abortion), a tone-deaf generation of (admittedly) extreme Watergate babies, and keen Republican messaging had savaged the Democratic Party. Indeed, for many Americans, Shirley Chisolm, Bella Abzug, and Gerry Studds had become the face of the Democratic Party in the same way that Todd Akin had become for modern Republicans. However, neither of these were quite fair. Much like Republicans, the national Democratic Party generally opted for more moderate figures. For all the mockery Carter endures from mainstream conservatives today, Carter won the 1976 Democratic presidential nomination by running as a culturally conservative, Southern moderate. During his term, he passed several fiscally moderate measures that modern Democrats would balk at (airline deregulation, common-sense energy policies, and zero-based budgeting), took several principled foreign policy stances modern Democrats would never evince (the Carter Doctrine), and chose to pass no healthcare reform rather than an unworkable plan from radical Congressional elements and a cartel of myopic labor unions. Democratic voters once again chose that relatively moderate candidate over the slimy, murderous ringleader of those congressional shenanigans, Ted Kennedy. Yet, Democrats took a beating.

The appropriate response to the 2012 election, according to Beltway politics.

The appropriate response to the 2012 election, according to Beltway politics.

After annihilating Carter and inflicting some of the nastiest Senate cycle losses in history, Republicans crooned that they had inaugurated a new era of one-party dominance. Political pundits even went as far to claim that Republicans had a permanent lock on the electoral college due to states such as California, New York, and Texas being solidly Republican and indeed, Republicans easily clinched electoral college majorities. Yet, after Reagan’s honeymoon, Democratic House majorities would eventually prevent serious adjustments to social spending and entitlements, sneak through tax hikes far larger than the Kemp-Roth cuts, and even implement a largely unconditional amnesty program. Narratives of supposed ideological ascendance and arguments about the zeitgeist of certain eras may be a useful heuristic for thinking about history, but when evaluating actual possible policy outcomes, the raw numbers on the ground are far more useful. The “Reagan Revolution” may have greatly influenced the way Americans spoke about government, but with solid Democratic control of America’s purse strings in the House of Representatives, did not result in actual downward adjustments to spending. In comparison, structural Republican control of the House of Representatives has already yielded several dividends for the right. Political observers from fifteen years ago would be shocked to see Democrats rejoicing and Republicans screaming in indignation after a deal that permanently extended 99 percent of the Democrat-reviled Bush tax cuts. As tiny and relatively insignificant as it may be in the grand scheme of the budget, the sequester represented the first absolute cut in discretionary spending since post-World War II demobilization almost 70 years ago. Most infuriating to Democrats, despite his electoral victory, Obama’s aggressive proposals for amnesty and gun control are largely DOA in Congress, an irritation probably familiar to Republicans who saw much of Reagan’s agenda in 1984 DOA in Congress.

After Democratic hopes of a resurgence collapsed in 1984 after nominating a candidate who went down in flames after proposing tax hikes (that the winning candidate would largely implement after winning), Democrats may have realized that in many ways, like the GOP of 2012, they were largely culturally alienated from the rest of the country. Many like to croon that the GOP will be forced to adopt Democratic social positions to remain competitive, like how many like to think that Bill Clinton drove towards the cultural center to win in 1992 and create a new Democratic Party. Certainly, Bill Clinton talked about social issues in a less frightening way for Americans than previous Democrats, but terms of actual policies, there was little movement towards the center. From Clinton’s extremely aggressive assault weapons ban, to his repeal of the Mexico City Policy, to repeated vetoes of partial-birth abortion, a procedure which by that time had been banned in almost all of the Western world, there is little to suggest that the “Clintonization” of the party did anything to moderate the social positions of the Democratic Party. Likewise, the flaming failures of the Mourdocks and Akins of the party show that the rhetoric of the Religious Right has become exceedingly outdated, but such a conclusion doesn’t necessarily poison every position they support. Many (leftists) argue that Republicans will be required to adopt orthodox left-wing social positions to attract the young, but the policy preferences of the youth are far more complicated.

The political preferences of young Americans are far more complicated than slavish adulation for Obama. For one, the vaunted Democratic preference advantage among young Americans shrinks the younger those Americans get. Although Obama won nearly 66% of Americans under 30, he won only around 60% under 24. In addition, in a nationwide poll of high school students, Obama only won 52%. In addition, even many (older) individuals on the right worry that something is deeply wrong with America’s youth, that they are simply completely untethered to the previous generation and vote Democratic because of a pathological leftist inculcated by modern society. However, increasing Democrat preferences among the young aren’t because millennials are simply “wired differently” or have values incomparable to their parents, but simply because so many millennials have parents who weren’t part of the electorate. Both Anglo-White and black voters aged 18-24 voted slightly more Republican than their parents. However, many new Hispanic voters expressed political preferences similar to their parents, a fact that skews the youth vote towards Democrats because in many cases, their parents are not voting citizens. In addition, with Latin American birthrates collapsing and the economic rise of Latin America, migration from Mexico has long-since turned negative, with immigration from the rest of Latin America decreasing. The once high fertility rate of Hispanic-Americans has recently collapsed, helping dash hopes among Democrats that a strongly Hispanic America will lead to permanent Democratic majority, especially since such a hope assumes that the voting patterns of Hispanic Americans will not change after the end of that immigration wave despite that being the experience of every other immigrant group in American history. One caveat exists: this feared cultural discontinuity and right-wing extinction can actually be seen among Asian-American voters. Middle-aged Asian immigrants, excluding heavily Republican Filipinos and Vietnamese, tend to express a moderate Democratic lean while young American-born Asians vote more Democratic than African-Americans of the same age cohort. However, with immigration from Asia tapering down and second-generation Asian-American birthrates being almost nonexistent, there will be no wild dash towards the cultural left for American society as a whole.

In addition, trends among the youth do not entirely favor one party. Same-sex marriage appears to be a legal inevitability, but to a radical from 1960’s Greenwich Village, the aspiration of so many LGBT Americans towards a form of traditional monogamous marriage might seem disappointingly reactionary. On the other hand, on a variety of left-wing sacred cows from an “assault weapons” ban to affirmative action to government paternalism (Bloomberg, soda, etc.), young Americans have proven much more hostile than their parents. A poll found that even though a narrow majority of older Americans supported an “assault weapons” ban, over 70 percent of younger Americans opposed such legislation. Even on an issue like abortion, where commentators like to imagine the youth being far more left-wing, public opinion barely shifts between generations. In addition, Pew Research poll even found that young Americans, even Hispanic-Americans, were more hostile than their parents and generally disapproved of an amnesty scheme, possibly an outgrowth of the severely diminished economic futures of today’s young people. As such, the current legislative agenda of the Democratic Party is comprised almost entirely of policies young Americans are largely hostile towards, amnesty and gun control.

Despite all of the doom and gloom, the future of the Republican party looks very robust.

Despite all of the doom and gloom, the future of the Republican party looks very robust.

In addition, the massive popularity gap between the two parties and the supposedly damaged brand is largely driven simply by low Republican opinion of their party. A Pew study found that less than 70 percent of Republicans have a positive opinion of their own party as opposed to around 90 percent of Democrats. Unsurprisingly, a Democratic base constantly enticed by a stridently left-wing President are more upbeat than a Republican base that twisted its nose for McCain and Romney. However, Republicans are united in one aspect – their almost universal disgust for the Democratic Party. Among independent voters, the parties are unsurprisingly both exceedingly unpopular, with Democrats holding a 4% favorability advantage. Although Republicans have a popularity gap to make up in the next few years, that gap is neither a wide chasm or insurmountable obstacle.

Lastly, left-wing policy ascendance runs into one major issue: arithmetic. Log-rolling is much easier with a constantly expanding pie. However, with an aging nation, one must often run to stand in one place. Even if American productivity growth matches that of postwar-boom and the Internet Age, a stagnant or shrinking workforce means that America will inevitably grow slower than it ever has before. The economic reality of a slower-growth United States means that the popular social programs Democrats promote will not be supportable on the tax revenues of the future. No matter how high taxes on the “wealthy” may rise, those new revenues will not be sufficient to sustain current entitlement programs, let alone yet-to-created programs that Democrats widely back. Democrats may find it exceptionally easy to promise middle-class Americans attractive social programs funded by the wealthy, but when the aging of America (fewer taxpayers, more dependents) makes it necessary to also burden middle-class Americans to fund those programs, Democrats will no longer be able to have their cake and eat it too in the arena of middle-class public opinion.

The vocabulary of the Left may very well be ascendant today. However, lessons from history and from modern-day polling do not suggest that the basic policy positions of American conservatism have gone out of date. Democratic triumphalism may surge as Democrats enjoy the intense satisfaction of seeing Republicans forced to speak in their language (future Republicans will need to find a way to deal with inequality), but like the Republicans of the 1980’s, modern Democrats may grow frustrated when such rhetorical dominance fails to translate into policy victories. There will be serious headwinds for the American Right to deal with in future, but the American Left doesn’t merely get a free pass. Although the Left may have fewer headwinds to deal with, the future of American politics will largely be determined by how adeptly each side adapts to the new American reality and deals with the new headwinds they will encounter rather than predetermined by some mystical demographic shift.

— Kirk Jing

Be the first to comment on "[Print] Not All Doom And Gloom"