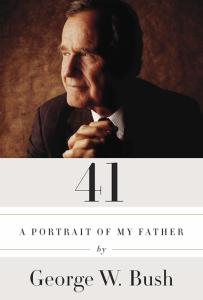

Because he had largely eschewed the public spotlight after the release of his 2010 memoir Decision Points, many were quite surprised to learn last year that former President George W. Bush had again picked up the pen to craft a very different sort of portrait than the paintings he had been producing. Entitled 41: A Portrait of My Father, this masterful biographical work on President George Herbert Walker Bush comes across as a genuine labor of love. Indeed, through his crisp and candid prose, Bush the Younger achieves his expressed purpose of writing “a love story,” as he told CNN’s Candy Crowley during an interview on “State of the Union.” In so doing, he not only provides readers with insight into his subject, but into himself as well.

First is of course the singular perspective that only George W. Bush as the author could provide in relation to his father—not only as a son but also as one who has likewise been elected to the Oval Office. In this sense, 41 is a book of unprecedented historical significance, for the Bushes are only the second father-son pair to be elected president after John Adams (number 2) and John Quincy Adams (number 6). This was in fact part of the impetus for Mr. Bush’s idea of writing an intimate account of the family patriarch’s life from birth to the present-day (along with the uncertain circumstances of his father’s health at the end of 2012 when he began the project). He relays this in a note at the beginning of the work and recounts a conversation with Dorie McCullough Lawson, the daughter of famed historian and author David McCullough. She mentioned to him that one of her father’s “great regrets” in researching his famed, Pulitzer Prize-winning profile of John Adams that there was “no serious account of him by his son John Quincy Adams.” Lawson then reportedly implored Bush 43 to write a book on Bush 41 for history’s sake.

It stands to reason, then, that the tremendous accomplishments of the author, like his subject, lend themselves to intriguing parallels found in their respective biographies—both in terms of their personal development as well as in their professional careers as dedicated public servants. This is another key reason why 41 makes for such an intriguing read. One prime example of how their personal legacies are equated is in parenting: how they each represent themselves as upstanding role models for their children to follow. Bush described his book as in part “a handbook on fatherhood,” explaining that “if somebody’s interested in how a person was a great father, even though he’s very busy, this book is such an example.” In fact, the author draws on three generations of the prestigious Bush and Walker family lineages to illustrate their clans’ deeply engrained values. Bush first highlights the strict and lasting sense of decorum and discipline emphasized by his paternal great-grandfather, the successful investment banker George Herbert “Bert” Walker, in an amusing story about one of his sons, Lou. When the young man once showed up intoxicated for a doubles championship match at their Kennebunkport tennis club, Bert Walker declared that rather than returning to Yale for the fall term as planned, Lou would instead be shipped off to Pennsylvania for the year to work in one of the coal mines that he owned.

Likewise, Bush 43 recalls how his grandfather, financier and later Connecticut Senator Prescott Sheldon Bush, was also a stern paterfamilias who “held strict views on moral issues,” but with a great singing voice and a shining “lighthearted side as well.” But perhaps most significantly, Bush the Younger illustrates the extent to which G.H.W. Bush truly “idolized his father” and how “in many ways, he patterned his own life on Prescott Bush’s: volunteering for the war, excelling in business, and then serving his fellow citizens.” And then, of course, Bush 41 subsequently passed on these values and words of wisdom to 43. The author eloquently encapsulates what Prescott Bush’s sagaciously taught his children, “that the measure of a meaningful life was not money but character. He stressed that financial success came with an obligation to serve the community and the nation that made prosperity possible.” Bush points out that like his own father, Prescott always made sure that he was able to remain consistently dedicated to his family, to charity, and to his local community. A final piece of lifelong advice of particular significance, that Bushes 41 and 43 learned from Prescott “was the value of making and keeping friends.” This trait is apparent throughout George H.W. Bush’s life from his days at Andover and Yale, to his military service, to the oil business, to his time in public service. He truly never forgot a friend.

41 clears up one controversy that has been an incessant yet inexplicable focus of the mainstream media—speculation on the nature of the bond between the two Bushes, which many have characterized as mercurial and stormy. Bush has stated in discussions with the media that he hoped his book would finally dispense with such persistent rumors about the two former presidents regard for one another as anything other than mutual love and admiration. Bush certainly accomplishes this goal in 41, which comes across as a genuine account of what the two mean to one another and how the proud son was greatly influenced and inspired by his dad. But with regard to influence, the younger Bush also clears up another oft-levied and equally ill-conceived allegation—that his father exerted undue pressure on the agenda of his son’s presidency.

As Bush openly admits, his father had an outsized personal and professional impact on him from the time he was a child growing up in Texas, and then during his roles in business, and finally throughout his years in the political arena. Yet despite this, his decisions were always his own, even when George W. took up residence at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. It is the opinion of your humble reviewer, however, that Bush’s book could have been further enhanced if the author had addressed some of the darker moments he experienced during his younger years, which he describes as when he “was young and irresponsible.” There is only one such incident that is mentioned in 41 and which is also found in Decision Points: the infamous, greatly overblown incident with his father after driving home drunk with his brother Marvin. As George Bush Jr. tells it, his father was able to express his profound disappointment and shame his son’s reckless behavior without even uttering a word. A retelling of their interactions during other incidents like this (and there were others, as described in Decision Points) surely tested their relationship.

For political reasons, the son naturally played down his father’s role as confidant during his time in office, but now acknowledges his significance as a counselor rather than a puppet master who weighed in and gave guidance on decisions only when asked. None of Bush’s picks for cabinet positions were proposed by George Bush Sr., even though a number had served in his administration. Rather, the son occasionally came to the father on personnel questions, including the selection Dick Cheney to be his running mate and the question of replacing Donald Rumsfeld as Secretary of Defense. Likewise, though many who were against Bush’s decision to invade Iraq accuse him of going to war to finish what his father had started during the 1991 Gulf War, he also reveals that this certainly was not the case. While he admits in the book that after the September 11 terrorist attacks, he borrowed the phrase “this will not stand” that the elder Bush used in response to Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait, he resolves that the judgment to go to war with the Iraqi dictator once again was entirely his own. Bush writes, “I never asked Dad what I should do.” Rather, as with so many other tough calls that he had to make as president, George H.W. provided him with reinforcement and moral support when they did discuss the issue. Bush 41 told the sitting Commander in Chief at Camp David over Christmas in 2002 that “you know how tough war is, son, and you’ve got to try everything you can to avoid war,” but agreed with his son’s assessment that “if [Saddam] wouldn’t comply,” he wouldn’t “have any other choice.”

Fundamentally, this short but highly worthwhile read is about legacy, a word that encapsulates both its purpose and its importance within the annals of history. It is unsurprising that Bush the Younger would want to write a book about his father’s remarkable life to bolster Bush the Elder’s historical image. Sadly, George Bush Sr.’s short, one-term presidency is too often overshadowed by those of the men who directly preceded and succeeded him. Equally tragic is that in addition to his relatively successful time in the White House being overlooked, so too has this humble man himself and his amazingly diverse and uniquely American life story. It is a story that desperately needed to be told and shared with the public. As his son notes, in both character and on paper, George H.W. Bush is unquestionably one of the most impressive and qualified men to hold our country’s highest office in recent memory. His résumé certainly does not fit the conventional mold of most modern presidents. Many including this author would argue that he was far more qualified than most men who have occupied the Oval Office, and especially those during the last century. His son pinpoints that the prominent positions George Bush Sr. held in such a diverse range of areas—oil executive, Ambassador to the UN and later Chief Liaison to China, Chairman of the Republican National Committee, Director of the CIA, and vice president—made him well-equipped to lead the nation.

Yet despite all that he has achieved in his life, George Bush Sr. is still humble. He is the same gregarious man, even going skydiving at ninety. 41 shows him to be a man with incredible humility and class, as well as a healthy, fun-loving sense of humor. As such, George W. Bush’s newest book is a captivating narrative account of the life of a remarkable individual, depicting the loving relationship between these two great men and leaders of our country.

At the opening of his presidential library at Texas A&M University in College Station, Bush 41 recalls how of all the important positions he had held in his life, “the three most rewarding titles bestowed upon me are the three that I’ve got left—a husband, a father, and a granddad.” But as anyone who reads 41: A Portrait of My Father will surely realize, George H.W. Bush is so much more than that: he is a great man and a true American legend.

Be the first to comment on "43 Reviews 41"