Editor’s note (2023): The Dartmouth Review is proud to present a history of Green Key weekend—required reading for any socially literate or historically conscious Dartmouth student. The late Joe Rago ’05, a legendary figure at The Review and The Wall Street Journal, made the most recent, extensive updates and added other relevant information, much of it drawn from primary sources and personal accounts.

In a 1951 column in The Boston Globe, Bill Cunningham of the Class of 1920 wrote: “It may come as a surprise to modern prom hoppers that [the original] Green Key Weekend had nothing to do with their sort of business. Instead of soft lights, hot music, and gentle dabbles in romance, it came straight out of the he-man’s world of blood, sweat, and leather.”

The origins of the modern Green Key celebration can be traced to 1899. The Class of 1900 put together House Parties Weekend, a four-day celebration at the end of May that featured sporting events and parties and culminated in a Junior Prom on Saturday night. During the Weekend, the upperclassmen invited dates from nearby colleges. These dates’ names were printed in the Daily Dartmouth on the following Monday.

Over the weekend, the women would reside in the fraternity houses while the brothers found lodging elsewhere. The administration required each house to hire chaperones to guard against lewd and lascivious behavior. Thus began the tradition of “Sneaks,” whereby Dartmouth men would try to slip past the schoolmarms and matrons guarding the upstairs in small hours of the morning. The most enterprising would often employ creative measures to sneak to the upper levels of the houses to rendezvous with their best gals.

During House Parties Weekend, the freshmen were not allowed to participate in the festivities and were barricaded inside the dining hall. Clearly, the freshmen took the brunt of the abuse at the College in those days. Famously, they were required to wear freshman caps, floppy beanies that Clifford B. Orr ’22, in a memoir of his freshman year, described as “absolutely [of] the brightest green … you can imagine. They [were] the same color [of] green as cerise is of red.” House Parties Weekend, the embryonic Green Key, marked the first weekend that the freshmen were allowed to remove their caps in public—although not before a considerable ordeal.

The week leading up to House Parties Weekend was known as “running season,” when every freshman was required to run out of sight when ordered to do so by an upperclassman. Orr recalled that the campus was “covered by bobbing green caps of disappearing freshmen.” They were also required to rouse the sophomores in the mornings and to run errands for the seniors during the afternoons.

The “freshman photograph” for Aegis was always staged in the days leading up to the weekend, and the sophomore class traditionally took it upon itself to kidnap as many of the freshmen as possible so as to disrupt the photo’s taking. Marauding bands of sophomores would prowl about campus, brandishing clubs and the butt-ends of revolvers, in search of prey. When a first-year was spotted, they would give chase and seize him; captured freshmen were tossed into the cellar of the ramshackle Phi Sigma Kappa barn. In Orr’s experience: “Sixty captives were there, tied hand and foot, and strewn on the floor. We were thrown down among them, and you can believe that we passed a wretched night, with the cold winds howling through the shattered windows, and shrieking through the cracks along the damp floor.” Orr went on to describe his harrowing escape and grueling trek back to campus. He thought, “it has surely been a grand and exciting time … and if the whole class doesn’t come down with typhoid fever from drinking streams … we shall consider ourselves lucky. Thank Heaven, though, it’s over.”

Of course, it wasn’t. At sun-down, a bugle would sound and all four classes would gather at the Senior Fence. Led by the band, they would assemble into columns (the freshmen last) and march up the College Hill to the Old Pine, where elite juniors would be inducted into the Palaeopitus senior society. A parade across campus would follow, which terminated at the center of the Green, where a huge keg was waiting. In the days of Daniel Webster, the cask was filled with old New England rum; in later days, it was filled only with lemonade. Palaeopitus would advance and drink, followed by the seniors, then the juniors. By this point, the fluid would be running low, and the Rush would begin. At the crack of a pistol the sophomore and freshman classes, laying in wait on opposite sides of the Green, would charge towards the keg and attempt to pull it back towards their respective sides. Pandemonium would always ensue, and several freshmen usually ended up unconscious.

Orr remembered: “If you have never been in a [R]ush, you do not know the feeling of endless pushing, panting, struggling, slipping, fearing every moment that you will be the next to disappear under the feet of … mad youths and be trampled.” Before the Prom, a final tradition would take place—the Gauntlet. The upperclassmen would line up diagonally across the Green. The freshmen would run between them while being beaten and flogged with sticks and the sting of belt leather. (Serious injuries would often result from seniors turning their belts around and whipping with the buckles).

Still, the freshmen took the Gauntlet in good spirits. For Orr’s class, “nothing very serious happened”—just “gashed and bleeding faces” and “two arms out of joint and a broken collarbone, nothing more.” Finally, the festivities ended with the ceremonial burning of the freshman caps.

Of course, the upperclassmen continued to revel at the Green Key Prom all the while. The tradition continued until 1924 when the faculty and administration decided to cancel it because of “alleged misconduct and rather wild behavior in the previous years.” It is generally believed that the ban on the Prom resulted from an incident involving Lulu McWoosh, a visiting woman who rode around the Green on a bicycle bereft of the traditional prom attire, or any other attire, after copious drinking. While students, no doubt, enjoyed the scene, the administration was not amused.

The Junior Prom did not return to Dartmouth for another five years. There is no indication that anything else filled the void during the heart of the Roaring Twenties, but, during this time, unrelated events transpired which would allow for the return of this festive May weekend.

In 1921, the Dartmouth football team left for Seattle to play the University of Washington. The Dartmouth team was greeted at the station by uniformed Washington students who took charge of baggage, bought refreshments, and served as guides. Until then, it had been a tradition of Dartmouth students to view visiting athletic teams with hostility. The warm welcome in Washington inspired the formation of a similar organization at Dartmouth, and, on May 16, 1921, “the Green Key” was born as a sophomore honor society.

The society underwent dramatic structural revision over the next few years, both in terms of the way it selected its members and in its function. Initially, it had three aims: entertaining representatives of other institutions; acting as a freshman rule-enforcement committee; and selecting from its ranks the head cheerleader and the head usher of the College. Only the first of these aims remains today. About two years after its inception, the society voted to turn its “vigilante function”—forcing freshmen to wear their caps—over to the sophomores at large. In time, the function of selecting the head usher and cheerleader was turned over to various College departments.

In 1927, at the faculty’s request, society members wore their uniforms of white trousers, green sweaters, and green caps with the key emblem during freshman week to help clueless frosh find their way around the College. Also, to meet the expenses of entertaining visiting teams, the society sponsored an annual fundraiser. In 1929, this became the Green Key Spring Prom. The party had returned.

The administration felt that the weekend would be better organized and take on an air of civility if the Green Key Society oversaw the activities. In 1931, the College banned fraternity house parties because of frequent occurrences of what it called “disorderly conduct.” At one point, President Hopkins threatened to ban Green Key festivities, writing in a letter to Inter-Fraternity Council president Albert Bidney ’35 that “the Green Key Promenade cannot be held unless definite assurances can be made that propriety will attend it.”

Still, Green Key weekend took on epic proportions. It became the font from which Dartmouth alums drew their most fantastic stories of life at Dartmouth. The Boston Herald and The New York Times carried accounts of the weekend and published a guest list of the largest yearly party in the Ivy League. The list was no small undertaking, considering that thousands of women from all over the Northeast made the pilgrimage to Dartmouth. The fraternities took on the enviable task of housing this flood of eager women. The Green Key Ball was forcibly brought to an end in 1967 after rioting broke out.

Drinking, then as now, was always an integral part of the festivities. Green Key provided the occasion for one of Judson Hale’s most famous anecdotes. Hale was a member of the Class of 1955 and the storied editor of Yankee Magazine; he was expelled from the College after vomiting Whiskey Sours on Dean Joseph McDonald and his wife during a performance of the “Hums.” Hums, according to Orr, was a “Dartmouth tradition, old as the College, I guess.” Each fraternity would compose a tune and perform it for the College at large, to be judged by the music department and other administrators.

Hums became a bone of contention as the years passed by and the songs became racier and filthier. The administration gradually became less and less tolerant of these amusing tunes and eventually began censoring them once the College went co-ed. In 1979, “Real Hums,” sponsored by the Inter-Fraternity Council, was introduced, free from the College’s red pen. Real Hums caught on for a while and was even reported once by Playboy magazine to be the best party of the year. Eventually, though, the tradition fell by the wayside.

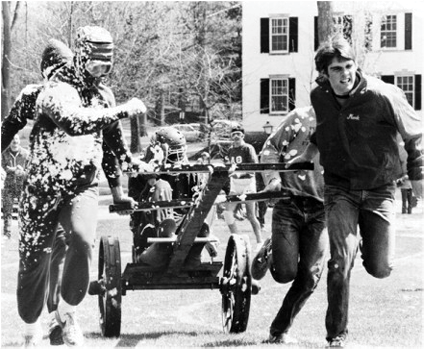

Gradually, the Gauntlet, too—for whatever reasons—faded away, though the ingrained traditions of ritualized beatings proved harder to stamp out. During the “Wetdowns,” newly elected student-government representatives would be pelted with vegetables, food, and debris as they ran across the Green. During the 1960s, a tradition of chariot racing took root. The fraternities would construct unsteady and unbalanced chariots, which new and intoxicated pledges would haul around a track on the Green while being assailed by eggs, condiments, flour, rotting vegetables, sacks of potatoes, beer cans, and other rubbish. The race ended when all the chariots were demolished. Eventually the administration forced the races off the Green and to a large field near the river. When the event finally became too violent near the end of the eighties, the chariot races came grinding to a halt.

Green Key has traditionally had no theme—it has long been simply a holiday weekend at the College for no reason. Only once in its illustrious history has it had a theme, and it was an unmitigated disaster. At the behest of Director of Student Activities Linda Kennedy, the College officially dubbed Green Key “Helldorado” in 1994. The tag honored the “Swinging Steaks,” a band the Programming Board had hired to play in the center of the Green. Students could also enjoy a petting zoo, a magician, a human gyroscope, and a moon-bounce. Needless to say, there was no theme the following year.

Today, though the most outlandish and violent traditions of Green Key have faded into obscurity, the spirit of the weekend lives on. Though the weekend is devoted to little more than revelry, partying, and hanging out, it has been reinvigorated over the past few years. The idea of Green Key has evolved into a celebration of spring for the campus—a great excuse for students and alums alike to enjoy both the fair weather and smooth beers. A staple of Green Key since the early nineties, despite a short interruption in the early 2000s, Phi Delta Alpha’s Block Party on Friday enlivens Webster Ave and sets the pace for the weekend’s festivities. Alpha Delta’s Lawn Party provides in that same strain an opportunity for daylight inebriation, despite the best efforts of Hanover’s finest.

As Clifford Orr wrote in May 1918, “[t]hese are happy days. The evenings are so warm and so perfectly delightful that we do our best to get our studying done in the afternoons that we might [fraternize] well before dark.”