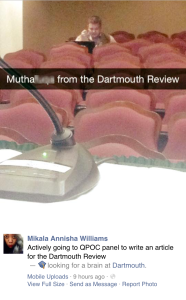

Our diligent and adventurous author, fearless as ever, on the job despite controversy from members of QPOC

When as a freshman I first began to check my Blitz account, I was puzzled by the myriad emails that cluttered my inbox. There was an email from some sort of Christian Fellowship, yet I am not Christian. Another came from the Women of Color Collective — I am not a woman of color. By the end of my fall term, I had settled into a few groups and clubs and learned to ignore the flood of emails that advertised groups and events utterly unrelated to my interests and identity.

As someone who calls himself an independent and a conservative, it never occurred to me to give any of the more liberal or identity-based events a second look. I felt no need to engage with a group of people who so obviously had such a different outlook on life and Dartmouth than I did. As a writer for The Dartmouth Review, I came into contact with this community at various third party events and protests. The Freedom Budget and the occupation of Parkhurst forced me to confront my opinions on the groups that make up the “radical” fringes of the student body. These experiences confirmed what I had suspected: my opinion was unwelcome and discussion of dissent was verboten.

Either in spite of this or out of a sense of intellectual curiosity, I decided to sign up for an OPAL-run program called Inter-Group Dialogues during my Sophomore year. I attempted to balance expressing my opinion with a sincere attempt to understand the community I was interacting with. While I felt welcomed there, I was distinctly conscious of my foreign status and the repercussions I would face if I were to be entirely honest during guided discussions.

As I have progressed in my career as a student and a person, I have made further attempts to understand groups with which I have little in common. Using the knowledge and terminology I acquired during the Inter-Group Dialogues, I tried to interact in a positive and productive way with individuals from these communities who were willing to reciprocate these intentions. This summer term, I have attended two panel discussions, a “Queer People of Color Panel Discussion on the Legalization of Gay Marriage” and a “Panel Discussion on Intersectionality,” as a reporter for The Dartmouth Review in an attempt to better understand the personal stories behind the emails I have for so long disregarded.

The QPOC Panel

I quietly entered the July 14 Queer People of Color Panel Discussion, subtitled Is the Legalization of Same Sex Marriage Enough, identified myself as a reporter for the Dartmouth Review, and took a seat towards the back of Dartmouth Hall room 105. A few hours after the panel, a friend showed me that one of the panelists, Mikala Williams ’17, had taken my picture as I sat in my chair and posted it to Facebook, overlaid with the words, “Muthaf*** from the Dartmouth Review,” and captioned, “Actively going to QPOC panel to write an article for the Dartmouth Review.” With the explicit intent to commit an act of journalism, I opened my mind and began to listen.

A sophomore man identifying himself as Cameron, President of Dartmouth’s chapter of the NAACP, moderated the panel, which consisted of Logan, Mikala, Kelsey, Amara, Zahra, and Dondei. All of the panelists were members of the class of 2017 and chose to identify themselves by their first names only and their preferred pronouns. All but two preferred female pronouns; Logan preferred male pronouns and Amara was content with either female or gender neutral appellations.

Cameron’s first asked, “What does gay marriage mean to you? Or how does it affect you?” The room filled with a bizarre, inexplicable laughter at the mention of the words “gay marriage.”

Mikala’s response, characterized by an aggressive tone and constant use of vulgar language, served as an introduction of sorts. She reiterated that all members of the panel identified as queer people of color (this characterization is often abrogated to “QPOC”) and stated, in reference to marriage in general, “I think that the… white institutions is so f***ed up.”

Kelsey took a softer approach, “I think that gay marriage for me is kind of comforting I suppose…. My problems with gay marriage would be that it goes beyond the ability to go get a piece of paper…. Just because the government doesn’t recognize your marriage doesn’t mean that your love doesn’t exist…. Thank you for letting me have this but at the same time, why did I have to need it?”

Zahra asserted that gay marriage “erases all other queer groups,” and that “The problem is that we seem to think of the battle as done now.”

Dondei echoed her statements, saying that when she encountered Facebook status about gay marriage, she thought, “Great, gay marriage passed, now white people can get married.” She clarified that when she thinks of society’s definition of gay people, she pictures, “two white guys, maybe early 30s….” She stated that, “We need to expand the idea of who is queer, who is gay.”

“I think about how segregation there was made illegal [but] there are still social structures in place that allow violence against people of color,” she said, “There are so many other social issues that are plaguing people of color.”

Kelsey expressed concerns that those who choose to avail themselves of the opportunity to get married could face social repercussions stemming from the formalization of their relationship. Mikala cut in to say that, “The issue is that the federal government is essentially saying, ‘F*** you, f*** your right to exist in a private society,’” a sentiment many conservatives would no doubt agree with, though perhaps in fewer words. According to her, the real issue at hand was not gay marriage but, “getting access to the means of production… so that you truly have the freedom to do whatever the fuck it is that you want.”

Zahra took their complaints about gay marriage to their ultimate conclusion, “What good is it having the right to marry if I am away in the courthouse or getting gunned down in the street?”

Amara changed the subject, “The hyper-visibility of this issue drowns out issues for people of other identities.” They continued, saying that gay marriage has been, “romanticized.”

Logan spoke up, saying that, “Marriage will not save me; it will not save me as a queer person, will not save me as a black person…” and continued listing his other identities which gay marriage could not save, though it was not clear what these identities so urgently needed to be saved from.

Kelsey then shifted the topic to fashion and photography, “It’s something that’s very pretty — the idea that people can get dressed up and go and spend their lives together. It makes a very pretty pictures and is something that is easy to legislate,” though it must be noted that gay marriage was “easy to legislate” only in the sense that balancing the federal budget will be a honest day’s work.

Mikala continued in this vein, “Literally being able to dress up and perform these gender roles is something that you will never really have access to in society … it’s really f***ed up.” She continued with her denunciation of society, calling Dartmouth a “white-a** institution.” Lamenting that many of her fellow students were not present to learn about her struggles, she asked, “How many people are in this room? How many people have access to this information that will save lives?” The answers to her questions were twenty-five people present, anyone at a Western college, depending on your definition of, “save lives.” Perhaps addressing what she meant by saving lives, she explained the many dangers that befall trans people today.

The “discussion” shifted towards the media, and Mikala gave a shout-out to The Dartmouth Review, “I thought of different news sources, maybe The Dartmouth Review, that have agency to reach lots of different people, maybe not as educated people, and frame… how we are perceived.” The crowd gave a round of snaps at the implication that the Review’s readers were “not as educated,” though the Review would like to thank Ms. Williams for her assertion that we reach lots of different people.”

Zahra attacked social media next, “We get to pick and choose what we get to see on our tumbler feed, because all I see on the media is a bunch of white people in their 30s getting married.” She criticized the portrayal of people of color in films, saying that they are “the first ones to die in horror movies,” and, “either hyper-sexualized or non-existent.” She then claimed that people of color were excluded from the LGBTQ movement, “The problem comes in when you are erased form the movement that you are basically the backbone of.”

All involved seemed to have a grandiose notion of what was transpiring. Mikala said that, “There should also be more media focus on what is going on here…. The violences on a personal level… that we have to confront. It’s not just the major cities. I think the worst…. I think there is a lot of f***ed up s*** that goes on at this school on an interpersonal level. There are violences and stuff that are going on within our own communities and our own homes.”

With this masterful attack on the “violences” of the world, the panel began to accept questions from others. Cameron, who was moderating the panel, asked, “If I’m an ally, what can I do to help besides changing my profile picture?” This drew laughter, and a series of curious remarks from the panelists.

Zahra gave a list of demands, “Do not force yourself into a space that was not created with you in mind. You cannot be upset if you don’t get the credit you deserve. You need to make sure that you step back and don’t let your voice drown out mine. You have to insert yourself into something that doesn’t necessarily concern you.”

Amara demanded that would-be allies, “Educate your damn self.” They said that, “If I’m trying to fight my own fight, I don’t have time to educate you.”

Dondei asserted that, “If someone calls you out, you need to sit down, you need to shut up, and you need to listen.”

The next question from the audience, though it was more of a statement, asked why there was not enough representation of people of color in the Women’s and Gender Studies Program. Another audience member called for action instead of discussion. Mikala said, “Trying to change institutions that are doing exactly what they were meant to do should not be the focus. Creating legitimate safe spaces… should be the focus.”

For the last question, a polite man in the audience stated that, “The problem that I had with the Freedom Budget was it is was mostly people putting their bodies on the line who were already vulnerable.” He received general accolades from the audience and panelists, and the event let out.

The Intersectionality Panel

This July 23 panel, organized by the Vox Committee, took place in Triangle House. As with the previous panel, I entered quietly and took a seat towards the back of the twenty-five person audience, identifying myself as a reporter for The Dartmouth Review. I was not oblivious to the murmurs that surrounded my presence, and I sensed a definitive hostility towards my presence. The panel consisted of three students, Asha, Mika, and Seon, and an Assistant Dean, Kari Cooke, and the event began with each student introducing herself.

Asha stated that she was there “to talk about the intersectionality of being a woman and a black person on this campus.” She described how she had, “experienced a lot of emotional turmoil,” her freshman year, and how, “It’s a feeling of consistently not being seen, not being acknowledged.” She said that she tries, “not to attribute those things to [her] skin color, but after a while… [it’s hard not to.]” She said that coming to Dartmouth “very much centered my identity on being a black woman.”

Mika described how she “didn’t really feel like a minority growing up,” but that after arriving at Dartmouth, “for the first time I was really conscious of how for the first time I felt either exoticized or invisible.”

Seon, who identified as, “an Ethiopian American black cis-gendered heterosexual woman,” said that, “As a lower class black first-generation woman, there are things I feel uncomfortable about.” She “viewed [Dartmouth] as a very white, elite culture,” and felt that “Dartmouth was not made for me, at all. It took me an entire year to transition.” She added that, “[my best friend and I] did not go to orientation week. We just stayed in our room and watched Orange is the New Black,” a choice which likely did not help the transition. Unlike many of her peers, she said that she, “decided to come to Dartmouth because of the Real Talk [protest].” She explained, “I came here because I appreciated that people were trying to work to improve the situation. A lot of these people face a lot of violence from this community. That told me that I should just keep silent too. Dartmouth is an oppressive place, but Dartmouth isn’t an isolated entity. Society is oppressive to women of color.”

Dean Cooke began, “I’m sure you’ve all heard of the patriarchy…” The room erupted with a mix of laughter, snaps, and mocking boos. The Dean hushed the crowd: this was not the message she was trying to communicate. At length she discussed a new word, “kyriarchy.” She explained that the patriarchy was a limiting concept and advocated a gender binary. As an alternative, she advocated using the word kyriarchy, derived from the Ancient Greek word for “lord” or “master,” to represent al systems of oppression.

More civil than the QPOC Panel, the Intersectionality Panel went straight to questions. The first questioned asked, “What you do to take care of yourselves…. How do you protect the individual parts of your identity and take care of them?” All of the panelists gave thoughtful and intelligent answer, largely devoid of the polemics and terminology of the QPOC panel.

Dean Cooke said, “For me, taking care of myself is about disengaging myself from the institutions that seek to define me. I believe that every single person has a divine spark of uniqueness that connects you to… your faith, your god.”

Asha described, “Changing what you draw your strength from, keeping in mind what is important to you, and realizing that you can’t change other people, only inform their opinions.” She also said that she took comfort in, “God, my family, and my Church.”

Mika said that, “Just being able to have meaningful conversations with people who will listen is something that’s really important to me at Dartmouth.”

The next question asked the panelists what the barriers to dialogue exist at Dartmouth. Asha argued that, “a lot of people are not even aware of the ways that they are privileged,” while Mika described how microaggressions against Asian Americans prevented internal dialogue. Seon discussed how the perception that dialogue is an attack on white people too often results in people getting defensive.

Dean Cooke interjected, “I don’t want to have to keep talking about the fact that I’m black. It’s draining.” Both Seon and Dean Cooke seemed to be unique voices within the discussions I attended. Their acknowledgement of two serious problems with the dialogue that occurs at Dartmouth was a rare occurrence in the far-left community.

Finding Meaning in the “Dialogue”

Dartmouth brings together a group of people from disparate backgrounds, many of whom struggled to fit in during high school careers either for lack of popularity or an excess of it. At Dartmouth, these individuals often struggle to find identity outside of academics and to work through psychological issues that were less apparent in previous years due to success in other areas. Students here find their places in vastly different ways, as they should. Unfortunately, not all ways of finding yourself are appropriate. My problem with the far-left community I have encountered at Dartmouth is not that they have strong identities and assertive beliefs, but that they ignore or attack the diversity of identities and beliefs around them.

Ms. Williams and her compatriots are living, shouting proof that Soviet-era Stalinist propaganda aimed at Western youth has at last established not only a formidable beachhead but a veritable fifth column within Western Universities. Her aggressive assertion of her identity, while it may make others feel uncomfortable, is not only her right but, if it really does make her life more fulfilling, her obligation. Unfortunately, she has sacrificed long-term fulfillment for short-term glory. Her repeated demands for more accommodation and her vociferous attacks on everything around her garner her attention and praise from certain sectors of this New England Liberal Arts campus, but they come at a cost.

She gets this attention because what she says is not entirely wrong. When she called Dartmouth a “white-a** institution,” she was, in some sense, right. While Dartmouth is likely far more diverse than many surrounding institutions and certainly the most diverse than it has ever been, it remains at its core an ivory tower in the woods of New England. Amongst the Ivy League colleges, it tends to be the least infested with radical leftist politics and perhaps the most quintessentially “preppy.”

What Mikala does not realize is that just because she does not identify with his culture does not mean that she must situate herself in opposition to it. The greatest Marxist lie that has perpetrated the minds of her and her fellow travelers is that two way of life cannot co-exist. She has built her identity not on a granite foundation of self-exploration but on a sand heap of hate for those who are not like her. Upon graduating Dartmouth, those who follow this temptation will realize that every other person on Earth struggles with a unique set of problems and feels isolated from what they perceive as the majority around them.

It seems to me it is the nature of man to think that his woes are external and not within. Whenever I hear someone blame “systems of oppression,” for something that is wrong in his life, I see a desperate person who is trying to place his faults onto the shoulders of others. While this is not healthy for an individual and those around them, it also has a far more sinister consequence. When a group of people begin to blame another group for all its ills, categorical hatred develops. When categorical hatred develops, ethnic, religious, or other sectarian violence occurs.

As Dartmouth President Ernest Martin Hopkins once wrote in a letter, “Personally, I believe that whether from the social, the educational or the religious point of view, the greatest weakness in American society at the present day is the disposition of individuals to avoid responsibility and to delegate this to outside agencies.”

Be the first to comment on "Finding A Place at Dartmouth: Thoughts on Diversity Panels"