Canes at Dartmouth have a history that predates their role in commencement. In the 18th and 19th centuries, canes were status symbols. The privilege to carry them was strictly reserved for upperclassmen, until freshmen started to challenge this rule. Freshmen’s eagerness to carry canes (and wear the accompanying top-hats) led to a tradition that has, long since, failed: the cane-rush.

The tradition was born out of the confrontation between freshman and sophomore classes over who had the authority to carry canes. Cane-rush gained notoriety in the 1870s. According to an account by Dennis Francis Lyons, Class of 1902, the practice began when two freshmen challenged the hierarchy and arrived on campus sporting canes. The sophomores would not stand for this indignity and wrestled with them for an hour until they had seized one of their canes. President Asa Dodge Smith took the other. The faculty then assured the freshmen that they should not feel intimidated by the sophomores’ violent reaction, and that the aggressors would be punished.

Undeterred, the sophomore class continued to cane-rush freshmen until three of them were suspended. To restore order, President Smith banned freshman from carrying canes, and the following year the cane-rush was banned as well. Though there were a few rushes in the intervening years, the tradition did not become popular again until 1882. The upperclassmen during that time “complained bitterly of the ‘mien and bearing’ of the Freshman ‘as he swings his law-protected cane.’” The wrestling fit’s return in 1882 was heralded by this amusing doggerel:

A tear was in the Freshman’s eye,

His little heart was filled with pain,

In vain he sued the cruel Soph

To please let him carry a cane

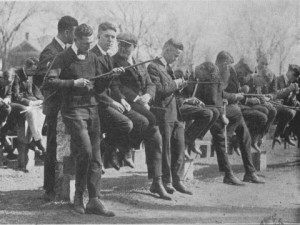

Cane-rush reached its peak in the fall of 1883. Wilder Dwight Quint, Class of 1887, recounted that year, the tradition was institutionalized and prepared for “in thoroughly scientific fashion.” On the day the event began, ‘87s formed a circle in the street, and townspeople and upperclassmen crowed around to witness the spectacle. The designated freshmen and sophomores shed their shirts, and with the help of the juniors, the freshmen covered themselves in olive oil. Three “giants” of the freshman class stood in the center of the circle, grasping a hickory cane. The ‘86s gave “a terrifying yell” as they poured out of Reed Hall toward the freshman group. The battle “raged for two mortal hours.” Many combatants “fell out unconscious” only to be revived by “buckets of cold water,” courtesy of the junior class. The spectacle lasted until the ‘86s finally succeeded in dragging the hickory cane back to Reed Hall. In Quint’s words, “discipline and the solidarity of a year’s acquaintance proved too much for untrained strength.”

As the practice died out, upperclassmen realized that if they could no longer pummel freshman for sporting canes, they could at least make them the exclusive domain of graduating seniors. Herbert Armes began the tradition of graduation canes at Dartmouth. Armes had the idea to create a cane from cheap, salvaged materials around Dartmouth and have his friends sign it. In 1885, Armes crafted a cane, with a shaft made from a “bannister taken from the rail around the piano platform in the old gym,” a head made of a stolen doorknob, and a ferrule made with a gas pipe. Armes’ cane was cheap and disposable; a memento of his time at Dartmouth rather than a fashion statement. He asked his friends to carve their names in it, though it was, in his words, “in no sense a class cane.” George Stetson, class of 1886, also wrote that he had “no recollection” of any class canes in his year, though he admitted that some of his classmates “may have had canes which were decorated by having initials cut in them.”

While some members of the Class of ‘86 would follow in Armes’ footsteps, it was the Class of ‘87 that seems to be the class that gave canes a place in Dartmouth’s history. An ’87, Mr. Bugbee called cane carving a “class custom” in a correspondence with a Dartmouth librarian in 1914. J. M. Gile ‘87, wrote that, for their graduation, it was “a class matter.” From the Class of ’87 onward, the graduating class would buy or make canes and encourage friends to carve their initials, names, or little symbols into the wood. In 1908, the administration even began creating a list of names and respective carvings to put on the record.

Class canes became commercialized in 1899 when Charles Dudley 1902 created the Indian head cane. His design was immediately in demand, prompting him to patent it and start a business with Alvin Leavitt, class of 1899. The two became proprietors of the Dartmouth Co-op, selling hand-carved Indian head canes. But student demand did not remain constant, and in the 1920s manufactured canes became the norm. The 1940s brought back interest in the Indian head canes, as the College commissioned Hans Brustle to handcraft them. According to an article in the New Hampshire Sunday News, each Indian head crafted by Brustle “must not only be identical with the others, but must match the Dartmouth emblem.”

In the 1960s, interest began to fade again; in 1963, the Co-op stopped selling the canes.

When the Indian head was banned in 1974, the traditional canes officially fell out of favor. To replace the symbol, Rev. Walter Traynham ‘57, dean of the Tucker foundation, proposed a carving of the college’s founder Eleazar Wheelock. Traynham sought to “provide an option for those students who might want to have a traditional cane,” while avoiding the use of any “symbolism distressing to Natives Americans.” The foundation contracted out the production of the canes to Jack Franklin of Windsor, Vermont and sold them to students for $20 (about $100 today). Franklin modeled the head of his cane on a portrait of Eleazar Wheelock from 1788.

Production stopped after a few years, however, as the head’s design, which resembled a sad puppet, proved unpopular. The stick’s stained oak wood looked like something out of a cheap residential staircase, nothing any self-respecting Dartmouth student would ever dream of carrying on his graduation day. The Indian head canes experienced a brief revival in the 1990s, when members of The Dartmouth Review carried them at graduation. They could not sport the original Dudley design, as its patent was still in effect, but they opted for a cane featuring a Mohawk Indian head.

The Dartmouth canes live on through the College’s senior societies. Around twenty percent of graduating seniors walk with canes affiliated with their Societies.During Commencement this spring, look out for the handful of sphinx, phoenix, griffin, and knight heads.

The traditional Indian cane has fallen out of grace. The canes became publically vilified when the NAD denounced a photo on a 2006 Dartmouth calendar that displayed an alumnus carrying an Indian head cane. The page displayed “a member of the Class of ‘56 proudly displaying an Indian head cane to an ‘06 at Commencement.” In fact, the alumnus was raising his cane to salute his daughter, as she lifted her Cobra Senior Society cane in return on the commencement stage. The College clearly thought the photo represented the never-fading pride that a father touchingly passed to his daughter. Instead, many viewed the photo as a display of historical offenses. The NAD community demanded a recall of the calendars along with a public apology.

The history of canes at the College has shifted shapes along with Dartmouth’s culture. Lovers of tradition rightly lament the disappearance of the old Indian head style. But it’s worth appreciating that the canes still live on, adding a unique flavor to our commencement and tying today’s students to generations past.

I have the Dartmouth Indian head from the senior cane of my father for the class of 1929. I hate to say my brother and I trashed the stick part in the woods as kids. My father screwed the head to the top of a large mirror in 1963 where it still remains today after I inherited the mirror. My kids thought it was an eyesore. I tried to explain the the history but it fell on deaf ears. I read your article in the February 7, 2016 issue of the Darthmouth Review concerning the history of the Senior Cane. I could not, however, have the ability to email it to my adult children. After all, it will pass on to one of them with the mirror. I guess I am asking if there is any way I can get that article? As a kid, there were four magazines that came into our home. Saturday Evening Post, Life, Playboy and of course, the Darthmouth Review. Thank you so much for whatever you can do.