Dartmouth is our introduction to serious personal responsibility. This leads us to think about most everything in the context of the College. We discuss alcoholism framed around College adults, sexual assault around drunken fraternity basements, and racism around College demographics. We put the blinders on and immerse ourselves in everything Dartmouth—the good, the bad, and the irrelevant.

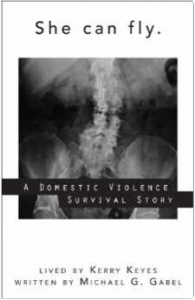

Books like Michael Gabel ‘09’s She Can Fly provide a refreshing—and difficult—step back. A story about trapped people in the real world, the book’s telling of Kerry Keyes’ story is an adrenaline rush, engrossing the reader in the decision-making, resilience, and courage of a domestic violence victim. Easily read in one sitting, the story begins when Kerry first met her abuser at nineteen years old until her decision to tell her incredible true story at the age of sixty-one. Gabel told The Review:

Kerry raised me. When my parents hired her as my nanny, I was an un-potty-trainable terror of a two year old. She taught me discipline. She taught me manners. She even taught me math…she was my best friend.

Gabel wrote Kerry’s personal account in the first person as a type of creative non-fiction, walking us through the vulnerability and helplessness of a domestic violence victim in a surprisingly gentle and honest way. He intimately creates her feeling of entrapment and relays her heartbreak and eventual redemption. Gabel said of hearing this story:

Sitting in Kerry’s living room day after day while she shared her life’s story — a story she had never shared in its entirety with anyone — was the most emotionally vulnerable experience of my life. And then to be entrusted as the keeper of that story is its greatest privilege. Writing about issues that I have never and, as a man, could never experience was difficult, but I knew if I could relay even a fraction of the beauty and clarity with which Kerry opened up to me then the story would speak for itself.

Gabel found himself—as a lot of us do—drinking too much, not studying enough, and consuming everything enjoyable all at once. “In 2008 I had just been suspended from the College and was at a loss for what to do with my time off, so I went to her apartment for some home-cooking and motherly consolation,” he explained. “Kerry couldn’t get the school administration off my back, or make my dad understand how alone I felt since he remarried and had the new baby, but she could love me.” The book shows Kerry as a caring woman that, despite being abused, raped, and imprisoned in her life, has shown nothing but maternal love again and again.

Kerry is an everywoman, a Midwesterner, private school educated and attending nursing school. With all of her newfound freedom, she begins experiencing new things and starts dating a local black musician, Wayman. Kerry’s dad forbids her seeing him and orders her to join the Navy to set herself straight. The abuse starts immediately after she ran away from home to live with Wayman. For Gabel though, Kerry was at the heart of the story:

I tried to never take a stance on [the racial aspect], to treat it as another element of the story…Wayman’s being black coupled with Kerry’s father’s racism serves as an example of the many circumstances that can lead women into abusive relationships. It’s not about how you get there that matters. It’s about how you get out…Violence has no target demographic.

With nowhere else to go—and a feeling that nobody would take her in even if she did run from Wayman—Kerry watches the years go by, having four children along the way. Her children become her life. She puts everything into raising her sons well in a wholly dysfunctional environment. By the time she gives birth to her third son, Kerry is living with two other women, both of whom have children fathered by Wayman.

She writes faulty checks to get food and cash back so Wayman can buy toys and fund his failed music career. He beats her mercilessly, using his fists, baseball bats, and fireplace pokers. She finds herself in the hospital with fractured vertebrae, broken bones all over her body, often passing out from the pain while Wayman kept beating her until he grew tired.

Wayman’s emotional manipulation keeps her trapped. Wayman and his mother tell Kerry the problem was hers and that she should do whatever she could to keep the family together. She starts to believe them. Every decision she makes is for her sons, and she disregards her own well-being. Gabel pointed out that the dearth of resources for abused spouses made such fictions actually believable:

Kerry didn’t have hotlines to call or shelters to run to. Domestic violence wasn’t even illegal until 1994. The only reason Kerry escaped, in fact, is because her situation got worse. But it saved her life. And yet the face of domestic violence has gotten worse since Kerry’s ordeal. Women aren’t leaving. They’re making excuses, holding out hope, and getting trapped in the endless cycle of abuse. They need to know how bad it can get, so they can get out before they get too far in.

Eventually, the faulty checks catch up with her, culminating in the Colorado justice system sentencing her to two years in prison while she was seven months pregnant. Five days after the birth, she is transferred to a penitentiary to begin her sentence. Prison provides a sort of respite from Wayman’s uncontrollable beatings. She finds a routine and for the first time since she was nineteen she has time to herself. She begins a school program, taking classes at a college nearby, and gets an early release.

Kerry returns to Wayman and her sons, the beating continue, and she does what she can. One night, Kerry finds large welts on her sons’ backs from Wayman’s belt causing a confrontation that leads a particularly gruesome beating. She drives herself to the hospital and makes arrangements to leave Wayman and go back to St. Louis.

It seems like she finally escapes the horrors of her time in Denver. She has her kids, she has a job, and she has control of her life. One thing leads to another and Wayman enlists one of his girlfriends to pick up Kerry’s kids and take them back to St. Louis. She cannot do anything but get her old job back and settle in the best she can while waiting for the parole board to accept her transfer. When it does not go through, Wayman forces Kerry to become a fugitive, hiding her in the attic and only letting her out to go write bad checks to run back the same scheme as before. It doesn’t take long before she is caught and put back in prison.

This stint is not as pleasant as the first. The prison now houses inmates addicted to drugs, getting their fix from a guard who sneaks product in and exchanges them for sexual favors. Kerry shoots down the guard’s advances, but one day he lures her into the projector room during a movie and rapes her, leaving her pregnant, emotionally crippled and too scared to report anything. The Colorado prison system, in an attempt to cover up the scandal and under intense pressure from Kerry’s lawyer, speeds up the process of putting her into a halfway house. Kerry’s lawyer, or, more accurately, her savior, keeps the state at bay, but in an attempt to keep Kerry silent, state police wait for Kerry at the halfway house to arrest her and send her back to the same prison she was in before.

She runs to California and becomes a fugitive using a new name and beginning a new life without her kids, her abuser, or her parents. She stays hidden in plain sight for seventeen years, using an identification card she finds on a public bus.

When the authorities find out she is a fugitive, they put Kerry back into jail to await sentencing. But it’s a different time now. People are more sympathetic to her case and more formal avenues of addressing domestic violence exist. She has numerous people fight on her behalf and, having not committed a crime the seventeen years she was at large, Kerry is released to live her own life under her own name, finally free from the shackles of prison and Wayman.

The book was released Tuesday March 25th and is completely free to read online, available on Amazon and hand held reading devices. The book is a registered 501(c)(3), making all (tax-deductible) donations go straight to maintaining the free online version and toward printing paperbacks for schools, women’s shelters and any and every resource center that will take them. Gabel commented on his decision to release the book in this way:

Oftentimes women in violent relationships can’t safely purchase or possess a resource like this, and it’s important that there be no access barriers – monetary or otherwise – between the book and the people who might need it most. That’s been a goal since day one…

[People who have read the book are] amazed not only by what Kerry went through, but also by her strength of will. Most importantly, they understand how trapped she was — how she couldn’t ‘just leave’ – which can be a hard concept to grasp for someone who’s never been in a similar situation. Sure they may know that domestic violence is horrible and pandemic (A woman is assaulted every 9 seconds, and 3 women are killed by their partners a day in the US). What they don’t know, however, is that, because of the emotional and psychological and physical weaponry deployed by an abuser, the longer a victim stays, the harder it becomes for them to leave. Until it’s virtually impossible.

Michael Gabel is a brother at the Phi Delta Alpha fraternity and often visits Dartmouth with his graduating class. He thanks many of his fraternity brothers and classmates at the end of the book. Of the six thousand dollar fundraising goal set on Kickstarter, he estimates that over half came from the Dartmouth community. Beyond telling Kerry’s incredible true story, this book serves as a testament to the Greek system’s ability to raise awareness on campus and national issues. Fraternity men are acutely aware of Dartmouth’s flaws and, as the Greek community has been arguing, the College’s best option to solve our very real problems is to work with fraternities. Marginalizing a vocal part of current and former students serves only to distract from the actions of individuals and stifle realistic progress.

The real richness of Gabel’s story is not in the plot, though, it’s in how he writes it. The first person narrative provides her point of view. We can tell that Gabel cares deeply for Kerry in the way he writes and in the raw emotion unloaded in these pages. Gabel and Kerry’s son Jermaine maintain a close relationship today. The book is a difficult read, but an important one. Read the book, donate if you can, and visit www.shecanfly.org for more information.

Be the first to comment on "Book Review of “She Can Fly”"