The history of recent protests at the College can be summarized by a quote from its most famous alumnus: “from there to here / and here to there / funny things are everywhere.” If they were not so telling of the present direction of the College, the events of recent years would seem comical.

Many of the recent events can be described as post-Lohse fallout. In March 2012, Andrew Lohse, a former SAE member, came out with allegations about hazing practices at that fraternity. After the College suspended him for cocaine use, Lohse decided to go to the press with an axe to grind, and his accusations appeared in Rolling Stone Magazine. The next few years would see debate about the fraternity system ramping up on campus, culminating with The Dartmouth’s front-page editorial calling for its abolition. But it was the visceral description of fraternity culture – “demonstrably untrue,” according to SAE’s lawyer – that was so polarizing. Lohse described, among other things, hazing, substance abuse, and sexual assault, some specifics of which cannot be described by this paper.

The fallout was enormous. More importantly, it heralded a change in tactics for many of Dartmouth’s activists. They began targeting Dartmouth where it would really hurt: admissions. In April of 2012, activists circulated a petition reading “I am concerned about the Greek System at Dartmouth” among prospective students during the dimensions period. Foreshadowing what would come a year later, they also interrupted a panel to deliver their message, which, according to the organizer Nina Rojas ’13, called for “structural changes by administrators that will fundamentally alter the way the culture works”. According to her, this could be as drastic as abolishing the Greek System altogether. But, even though this was a very visible event, it was the events taking place one year later that would be known as the “dimensions protest”.

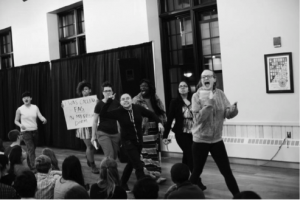

RealTalk Dartmouth, a group formed in early 2013, had planned to hold a kind of info session for prospective students in April of that year. When they saw “low prospective student turnout,” the group blamed, “the suppression of dissent at Dartmouth,” rather than the obvious lack of interest. In response to this, they decided to crash the final dimensions show. “It happened last year, it’s happening this year, and will hopefully happen every Dimensions until the College changes…. And by the looks of it, I think it’s working,” said one student about the protest. Shouting claims of homophobia and racism on campus, they pushed their way into FoCo, injuring one student at the door, and stopped the show. They were finally shouted down, perhaps surprisingly, by prospective students shouting, “We love Dartmouth.” After significant uproar on campus, some disparaging comments about the protestors on the website “Bored@Baker,” and the protestors disrupting a faculty meeting on the topic, classes were cancelled for a day.

Over the next year there were a few notable protests. In one instance, a group of students led by former professor and career instigator Russel Rickford staged a “die-in” at a speech by former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert, accusing him of war crimes and other atrocities. Ironically, Olmert is known for his far-left politics and his corruption. In February, activists released what they called the “Freedom Budget” with the goal of “redistributing power and resources in a way that is radically equitable.” Specific proposals included establishing a minimum required percentage of students of color for each matriculating class. The students demanded the administration respond in one month.

Even though they had received a response from President Hanlon, they occupied his office in early April, demanding that he lay out “first steps to enact the budget.” They stated, “Our bodies are already on the line, in danger, and under attack at Dartmouth. We are now using them to occupy the President’s office until he accords us the basic respect of serious, point-by-point, actionable response.” Needless to say, the occupation ended two days later without such a response.

Another protest that made national news came a year later, when activists found out that they could attack frats and cultural oppression at the same time. Pursuant to this, they protested a “Derby” party at KDE, accusing it of racism, and got into a shouting match with the student body president, a black man. The next year, KDE changed the theme.

This trend of agitation continued as fall moved into winter, culminating with the infamous invasion of the Baker-Berry library in November. After a sparsely attended vigil on the green, student activists (The Review uses that term loosely) affiliated with Black Lives Matter felt that something had to be done to change the apathy and disinterest on the part of the rest of student body, who were engaged in studying for finals. It is perhaps telling that the BLM activists felt no need to do the same. Regardless, clamorous BLM protesters poured into the library, justifying their disruptive protest by arguing that their emotional safety trumped any right that the studying student had to peace and quiet. Chanting and shouting, the protest soon devolved (or depending on one’s perspective, showed its true colors) into intimidation.

Protestors surrounded students and harangued them, reportedly reducing at least one student to tears. Undisguised racial hostility pervaded this action, and protestors shouted things like, “F*** you, you filthy white f***s!” and, “Filthy white B****!” Students in the library who refused to listen to or join in their shouting were shouted down: “Stand the f*** up!” Although the protest was negatively received on campus, the protestors achieved at least one of their goals. Apathy on campus regarding BLM definitely went down, although at least some of this apathy was replaced by contempt. After news of the library invasion spread, the college suffered a PR nightmare. Angry at the lack of disciplinary consequences for the BLM activists, alumni began making angry phone calls to the college and withholding donations. President Hanlon even reputedly received an earful at a Manhattan fundraiser.

Most recently, the Dartmouth College Republicans put up a bulletin board at Collis drawing attention to national police week. The day it was put up, Black Lives Matter activists tore it down and put up a replacement in violation of Collis policies. No students were punished for this act, and it was again reported on in the national news media.

Such behavior would be disturbing in isolation, but when they become an accepted and even expected form of student activism, they threaten the Dartmouth community and its climate of free debate.

It is not difficult to see why the campus left continues to pursue these tactics: they work. The left knows that the liberals in the administration are made uncomfortable by student activism and will make concessions in order to secure short-term calm. But in doing so, the administration has allowed its policy to be dictated by the radical elements in our student body. He who shouts the loudest is afforded the most influence, given the greatest chance at serving on college policy commissions, and accorded the most respect by administrators. It is deeply ironic that the aftermath of these events is always a call for more dialogue and discussion. Dialogue, at least as the Review understands it, always requires more than one party.

Be the first to comment on "A History of (Re)Activism"